| République Australienne Australian Republic Australie Australia | |

|

|

| Flag | Coat of Arms |

| Anthem La Marseillaise | |

| Motto Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité (Liberty, Equality, Fraternity) | |

| http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7d/Australia_(orthographic_projection).svg/220px-Australia_(orthographic_projection).svg.png | |

| Capital and Largest city | Bonaparte |

| Official languages | French |

| Demonym | Australien, australienne |

| Government - President |

Unitary Presidential Republic xxxx |

| Establishment - Colonisation - Self-Government - Union - First Republic - Military Provisional Government - Second Republic |

26 January 1791 1 January 1826 26 January 1908 14 July 1923 16 March 1942 3 May 1949 |

| Area - Total |

7,617,930 km2 2,941,299 sq mi |

| Population - July 2007 est. Density |

22,446,272 2.833/km2 7.3/sq mi |

| GDP - Total - Per capita |

2011 estimate $851.170 billion $38,910 |

| HDI | 0.970 (high) |

| Currency | Australian Franc (Franc Australien) (FAU)

|

| Time zone - Summer (BST) |

UTC+1 (UTC+2) |

| Internet TLD | .au |

| Calling code | +61 |

The Australian Republic (République Australienne) is a large Francophone country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent (the world's smallest), the island of Tasmania, the archipelago of New Caledonia and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Neighbouring countries include Indonesia, East Timor and Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée to the north, the Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu, and New Zealand to the southeast.

A prosperous developed country, Australia is the world's thirteenth largest economy. Australia ranks highly in many international comparisons of national performance such as human development, quality of life, health care, life expectancy, public education, economic freedom and the protection of civil liberties and political rights. Australia is a member of the United Nations, G20, La Francophonie, OECD, APEC, Pacific Islands Forum and the World Trade Organization.

History[]

Pre-History and Colonial Era[]

Approximately 40,000 years ago, the Aborigènes d'Australie first arrived in Australia, probably with migration across the land bridge (now submerged) and short sea crossings. The Aborigènes d'Australie were primarily hunter-gatherers.

Australia was discovered by Europeans in 1771 and the colony of Nouvelle-Hollande was established in 1791 as a counter to British influence in the South Pacific. During the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte, Nouvelle-Hollande was renamed Terre Napoleon. The capital city Louisville was renamed Bonaparte.

During the Napoleonic Wars, the French colony of Nouvelle-Hollande fought a brief war with the British colony of New Zealand. The Australians consider the war to be a draw, however the French colonists failed to achieve any of their war aims. During the rest of the 19th century, other colonies were established. During 1884, the colony of Nouvelle-Guinée Française was established on the south east of the New Guinea island. It was notionally administered from Australie-Tropicale.

In 1908, the Union d'Australie was established. The Union Government has control over domestic policy, while foreign policy and defence were under French jurisdiction. Two military forces for Australia were founded, the Armée de terre d'Australie and the Marine de la République australienne.

Six years later, France declared war on Germany. By that action, Australia was at war with Germany as well. To fight in Europe and the Middle East, the Légion Australienne (Australian Legion) was organised from volunteers. Another force fought and defeated the Germans in New Guinea. The first battle successes of the Marine de la République australienne and the first Australian military aircraft. The Australian cruiser Ville du Nouveau Québec sank the German raider Emden 9 November 1914. The Légion Australienne did not mutiny in 1917, and fought with great success on the Western Front.

The war provided the path to full independence for Australia. A constitutional convention wrote the Constitution of the First Australian Republic. This was passed on Bastille Day 1923 and the Australian Republic was proclaimed.

First Republic[]

The First Republic was hit hard by the Great Depression, and by political indecision. Over its 20 years of existence, the average government lasted twenty months. In 1939, Australia declared war on Germany and dispatched the 2eme Légion Australienne to France and the Middle East. The fall of France precipitated the fall of the First Republic. After the fall of France, some Australians willingly served Vichy, some went into POW camps in Germany, while others escaped at Dunkirk to join de Gaulle's Free French. At the same time, the Japanese were moving south. The Prime Minister, Robert Meignot (with an already slender majority for his Parti Nationaliste d'Australie) had lost the support of the Partie Agricole d'Australie and the support of his own party. He was forced to resign, and was replaced by François Gué from the Parti socialiste d'Australie. He was in turn replaced by the pro-Vichy Jean Blanchard. Blanchard proclaimed his loyalty to Petain, and made an alliance with Japan and Germany. Blanchard also suspended the Constitution. Japanese and German ships could refuel at Australian ports. The loss of two Australian ships at the Battle of Mers-el-Kébir initially induced people to support the pro-Vichy Australian government, but over time, German actions in France, stories of de Gaulle's Free French (spreading in spite of a censored press), the suspension of civil rights, and the fear of Japan all weighed on the government. While the Marine de la République australienne was pro-Vichy, the Armée de terre d'Australie was more Gaullist. Defeat in 1940 stung them badly, as did the fact that their comrades were being held in German POW camps. The exploits of the Australian Free French also added to the support for the Gaullists.

The GMPRA[]

After the fall of Java, the Gaullist officers acted. Proclaiming "la patrie en danger", the seized the key governmental and communication points of Ville d'Australie. Prime Minister Blanchard was arrested, and the Gouvernment militaire provisoire de la République australienne (Provisional Military Government of the Australian Republic) was instituted. Formally, the President and National Assembly were kept in place, but real power rested with the junta led by Général d'armée Thomas Bertrand, who was appointed Prime Minister and Leader of the Government.

The new government set to work quickly, inviting the United States armed forces to Australia, and expelling or interning all Germans and Japanese. French citizens were required to swear and oath of loyalty to the Free French or be interned. Australians in Britain were infiltrated into France by the SOE to aid the resistance. In a daring move, three MRA ships broke out of Toulon harbour and made it to Malta. There they operated under British/Free French Command. Australian forces fought in New Guinea, and Timor against the Japanese. Australia's Gaullist government effectively had two armies. Their European Army fought with the Free French, and was equipped largely by the US and Britain. The Home/Pacific Army was largely equipped domestically (with some US assistance) and fought beside the United States and New Zealand. Australians landed in France on 6 July 1944, and marched into Paris on 25 August 1944.

In the meantime, some Australians continued to fight on the German side both with Vichy and with the German forces including the Légion des Volontaires Français and the 33. Waffen-Grenadier-Division der SS Charlemagne (französische Nr. 1). Australians also served in the Milice. At least 20 Australians fought on the German side in the Battle of Berlin.

At the end of the war, Australia was among the nations represented at the signing of the Japanese surrender. At this juncture, Australia and France stood together as equals. After the war, the GMPRA wanted to continue in office. By 1947, the people were demonstrating for a return to democracy. A new political force, the Parti libéral-démocrate d'Australie led by Robert Meignot gained substantial support. It was clear to Général Bertrand that the Gaullist officers couldn't stay in power. He beleived they were very popular, but would need democracy. To that end, the Gaullists formed a new political party, the Parti national-républicain d'Australie. Along with the Socialists, the Liberal Democrats and National Republicans would be the forces of Australian politics.

The Second Republic[]

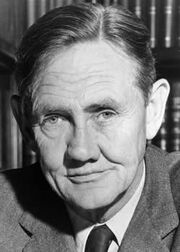

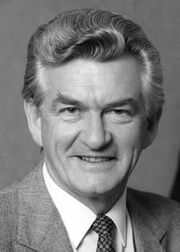

Robert Meignot (Nationaliste, Libéral-démocrate), eleventh Prime Minister of the First Republic, first President of the Second Republic (1949-1964). Longest serving President of the Second Republic.

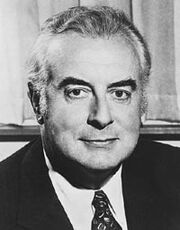

Jean Grosvenor (National-républicain), second President of the Second Republic (1964-1969).

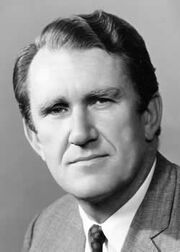

Xavier Molyneux (National-républicain), third President of the Second Republic (1969-1974)

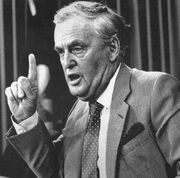

Guy Willmot (Socialiste), fourth President of the Second Republic (1974-1976). The only President to be impeached.

Marcel César de La Baume Le Blanc (National-républicain), fifth President of the Second Republic (1976-1979), the only unelected President of the Second Republic.

Yves Petitjean (National-républicain), sixth President of the Second Republic (1979-1983), notorious for his attitudes towards civil and political rights

Robert Fayette (Libéral-démocrate), seventh President of the Second Republic (1983-1995)

The 1947 Plebiscite on democracy received an overwhelming "Oui" vote. The "Non" vote registered less than 5%. The next year saw the passage of a referendum on a new Constitution, and Presidential elections. These elections would elect an executive President with strong powers and a five year term. Robert Meignot convincingly won the election and became the First President of the Second Republic which was proclaimed at his inauguration in 1949. Robert Meignot served for three terms as President. During this time, Australia saw excellent economic growth. Its foreign policy was extremely close to France and the United States. Australian troops fought in Indochina until the end in 1954.

Australia's closeness to France included nuclear cooperation. Australian uranium provides much of France's energy, and the material for France's nuclear weapons. France in turn allowed Australia access to French nuclear technology under a Pact of Peaceful Nuclear Cooperation (Pacte de coopération nucléaire pacifique) signed by French President Charles de Gaulle and Meignot in 1959 in Bonaparte. During the visit, President Meignot famously declared "I am French to my boot straps!". One result of this "peaceful" nuclear cooperation was the development of Australian nuclear weapons.

The Liberal Democratic policies of freedom of trade, both internally and externally, led to a period of sustained economic growth. Low unemployment, and a minimal welfare state bought low levels of crime. Australia during this time remained very religious. Australia became known in the Francophone community as a "land of opportunity", and immigration increased. After the war, a large number of Frenchmen came to Australia (a migration known to historians as La deuxième immigration). Grand national projects such as the Le plan d'aménagement des montagnes de Milou (Snowy Mountains Scheme) and the nuclear power program led to cheap electricity, and a sense of national pride. Unlike France, Australia experienced no great destruction during the war, indeed, Australia industrialised during the war. After the war, the government oversaw a process of conversion in which armament industries were turned to civilian production. A result of this is the fact that Australia now has a major automotive industry. Major French names such Citroën, Peugeot, and Renault populate Australia's roads. Australia also continued manufacturing aircraft, with the leading company being Technologies aérospatiales de l'Australie. Australia's aviation industry has close links to Eurocopter, MBDA, and Airbus. TAA's main competitor is Avions Marcel Dassault d'Australie.

Inspired by the Viet Minh, parts of Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée began to rebel against Australian colonial authority. The first attack of the FLPNG took place in 1956. Soon after, the Foreign Legion were moved into the province to supplement the Gendarmerie. Fighting intensified as Indonesia provided weapons to support the FLPNG.

During the 1960s, the war between the two Vietnamese states increased in intensity, and the United States called on its allies in the Asia-Pacific to assist South Vietnam. Australian veterans of the Indochina campaign had been in Vietnam under CIA contracts since 1957. During 1964, the United States requested Australian advisors be sent to Indochina. A training team of 200 personnel arrived in Vietnam in July 1964. Later that year, after the American Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, Australian combat forces were requested. During this time, the 1964 Presidential Campaign was in full swing with the Gaullist Parti national-républicain d'Australie and the Parti socialist d'Australie campaigning against the war, while the Parti libéral-démocrate d'Australie of Robert Meignot argued in favour of fighting communism in Asia. Whatever the merits of the argument, the Australian public feared another defeat in Vietnam, and the National-républicains swept into office with their leader, Jean Grosvenor (an Armée de l'Air d'Australie veteran of World War II) becoming President.

The new National-républicain administration stepped up efforts against the FLPNG in Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée, increasing Australian Army numbers to twenty thousand, and Gendarmerie numbers to twenty five thousand. Grosvenor promised that Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée would remain Australian. Although the Army and Gendarmerie fought with great skill, the FLPNG retained the initiative. The war also reduced the support for Australia in global affairs. Even France, Australia's closest ally, was calling for an Australian withdrawal. By 1968, Australian conscripts were fighting in Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée. In 1969, Grosvenor lost the endorsement of his party for President. He was replaced by the more moderate Xavier Molyneux whowas duly elected. He did withdraw conscripts from Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée and began talks with the moderate (non-violent) pro-independence groups in Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée.

The National-républicains reoriented Australia's foreign policy. They called their foreign policy "L'indépendance dans la force" (Independence with strength). The National-républicains feared the Communist advance in Vietnam, and viewed the French defeat in Indochina and Algeria as evidence that a big power alliance would not work. This contrasted heavily with the view of the Libéral-démocrates who favoured a closer relationship with the United States. They distanced Australia from the US, and the UK. The relationship with France was still close, but changed and became more equal. Requests from France to assist in Africa were always refused.

On the economic front, Australia was still doing well under the Gaullists. The war in Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée did not provoke trade sanctions or divestments. The National-républicains embarked on several infrastructure projects including ports, highways, and railways. In addition, the National-républicains initiated a programme of rearmament. The rearmament programme was carried out in accordance with the National-républicain foreign policy and their view of the global situation. It included extensive re-equipment of the Armée de l'Air d'Australie with greater numbers of supersonic fighters such as the Dassault Mirage III and (then in development) Dassault Mirage F1. Australia also gained a nuclear strike force with the Dassault Mirage IV replacing the Sud Aviation Vautour. The Armée de terre d'Australie received new AMX-30 tanks. The Marine de la République australienne received Daphné class submarines, and Suffren class frigates. All of these projects were costly, and Australia's national debt roughly doubled under Grosvenor and Molyneux to 100 billion francs.

The failure of the Molyneux administration to make any progress in Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée combined with the economic problems stemming from the oil crisis of 1973 sealed the fate of the Gaullists and ensured the election of the one candidate who promised real negotiation for independence for Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée and a solution for the country's economic problems. Guy Willmot was elected as the Socialist President of the Australian Republic in 1974.

Willmot moved quickly in Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée towards negotiations with all factions. Australian combat forced began to withdraw from the province. By the end of 1974, and agreement had been reached for independence in 1975. Independence was proclaimed on 16 September 1975. A unit of Gendarmes remained to advice the police, and a group of soldiers remained to advise the new FAPNG and to patrol the PNG-Indonesian border. The agreement was not all happy, however. It was deeply unpopular with the right of Australian politics, and PNG soon became mired in tribal violence.

On the social front, the Willmot administration broke decades of Catholic social conservatism. The first policies favouring the Aborigènes d'Australie were put into practice. Government subsidies of the arts increased substantially.

On the economic front, events were to prove once again, that when the world sneezed, Australia would get a cold. The 1973 Oil Crisis hit Australia hard, as did inflation in the countries with which Australia traded heavily. The Willmot administration came into office with schemes for government-funded industrial and mineral development. It was hoped that these would reduce unemployment, and restore Australian ownership of resources and industry. The vast spending of the National-républicains and the financial crisis caused interest rates on Australian Government securities to rise. Interest rates throughout the economy rose, as did inflation, prices, costs and wages. Unemployment was on the rise as well. In addition, Australia's credit rating dropped from AAA to AA. Given these circumstances, most governments would rein in spending, but some dreams are impossible to surrender.

The Willmot administration's finances were unorthodox in many ways, not merely because of the large preexisting debt and the large projects, but in the way they raised money. Finding loans is normally the responsibility of the Ministry of Finance, but the Willmot trusted a loan for $4 billion to the Minister for Minerals and Energy, Rene Colbert. Colbert was an economic nationalist and thoroughly dedicated to chasing foreign companies out of Australia's mining and energy industries. His schemes included natural gas pipelines and more extensive uranium mining and milling operations (Australia's uranium milling and processing capabilities were small, and Australia was primarily a uranium ore exporter). Traditional centres of finance like Paris, London and Wall Street wanted higher interest rates than the Willmot government wanted to pay. In addition, the oil crisis led to Arab nations accumulating large reserves of "petrodollars" which they wanted to invest (or so it was perceived). The securities of a Western government seemed to be a good investment.

To this end, Rene Colbert procured the services of a Pakistani commodities broker, Tirath Khemlani. Khemlani claimed to have contacts with access to the vast amounts of petrodollars the Australian government needed to finance its projects. In fact, this wasn't the case but this was not known to Colbert. For months, Khemlani would telex Colbert stating that the deal was in hand, and every time, it would fall through. Eventually, the government, needing to raise a routine loan on Wall Street, had to withdraw Colbert's authorisation to raise loans.

All government loan raising must be approved by an Ordre-dans-Conseil présidentiel (Presidential Order-in-Council), which is a legal document. A cabinet decision will not suffice. Unless for temporary purposes (i.e. an unanticipated cashflow shortfall or spending blowout), a loan must be approved by the Conseil d'emprunt (Loans Council, consisting of the federal government, a Senate group, and the provincial Prefects, who coordinate the nation's loan raising to best preserve its credit). Nevertheless, Colbert went on raising loans.At the same time, the Finance Minister Jean Caillier was (without any authoriation) had a businessman from Rennes in Nouveau Bretagne looking for loan money.

In time, these activities came to the attention of the civil servants at the Finance Ministry, the press, and the other two major parties. A Senate election in 1975 had left the Senate under the control of the National-républicains and the Libéral-démocrates. Government was therefore already very difficult. The Socialistes were also losing control of the National Assembly. Willmot responded by sacking Callier and Colbert, and this mollified the Senate for a while, but public discontentment was rising, and confidence in the government was at an all time low. Given calls from the grassroots for action, and the apparent illegalities of the government's action, the Senate impeached President Guy Willmot.

A combined sitting of the National Assembly and the Senate chose Nouveau Bretagne farmer and politician Marcel César de La Baume Le Blanc from the National-républicains.

Great hopes were vested in him, but his administration is widely seen as an economic and foreign policy failure. Few of the policies of the Willmot administration were reversed, and almost none of the reforms contemplated were put into action. Historians say this was because Marcel César de La Baume Le Blanc had little against the Socialistes (he was from the left-wing of the National-républicains). His campaign consisted of the negation of Willmot, without seriously opposing his policies. In 1978, the Libéral-démocrates pulled out of the coalition, and government effectively broke down for an entire year. The break from the National-républicainsv did the Libéral-démocrates no real good, as the next Presidential election was won by Yves Petitjean, another Gaullist.

Under Petitjean, economic matters stabilised, and Australia was put back on the path of economic growth. Petitjean was from the right-wing of the Gaullists, and in economic matters had an easy relationship with the Libéral-démocrates. Real estate became more of a growth industry. Government services in education and health improved. On civil rights matters, the Petitjean government had the worst record of and Second Republic government. The Gendarmerie often resorted to force at demonstrations, even peaceful demonstrations. Petitjean also advocated the sale of Australian-made and French-designed arms to South Africa in violation of the UN embargo (arguably the production licenses with Aerospatiale, GIAT, and Dassault were also broken). Protests against this supply of arms were common. They even took place in France. The French companies responded by donating their Australian royalties to the ANC (on which they took a tax deduction!). Petitjean offended the Western world in other ways. He called for a free, independent Quebec and suggested that France should cede their Pacific Islands to Australia. Needless to say, the federalist Prime Minister Trudeau (a fellow Francophone) and President Mitterrand of France were unimpressed. In a landslide, the Gaullists were removed from office in the Presidential election of 1983 and the Parliamentary election of 1985.

Government[]

Australia is a unitary presidential republic. It has previously been a directly governed French colony, a self-governing French colony, a union of self-governing French colonies, a parliamentary republic and a military dictatorship. Australia's system of government is based on that of France and the United States. The Second Republic has been known for its political stability.

Executive[]

The chief executive body in Australia is the Conseil des ministres d'Australie (Council of Ministers of Australia). The Council meets regularly to give legal sanction to the decisions made by the Cabinet. Although the Cabinet and the Council of Ministers have the same members, they are different bodies. Cabinet is an informal body with no legal standing. It's purpose is to debate and decide government policies. The Council of Ministers is a formal body prescribed in the Constitution as the executive body of Australia. The President of the Council of Ministers is the President of the Australian Republic. The President of the Australian Republic is simultaneously the head of state and the head of government. He has the following powers:

- Granting assent to laws.

- He has a limited veto power. He can veto a bill extending the term of the National Assembly or the Senate, and can veto an unconstitutional bill. He can also refer a bill back to Parliament for another reading (but can do this once only).

- Commander in Chief of the Forces armées de la République australienne.

- The President can order a nuclear attack.

- The power to suspend/reduce criminal sentences.

- Basic control over government policies and appointments.

The Senate can impeach the President by a super-majority vote, but it must find that the President and his Administration has acted unconstitutionally.

Under the President and Vice-President, there are the Ministers. The Ministers control specific government departments. They are appointed by the President, and can be dismissed by the President or impeached by the Senate. Ministers must answer questions before the National Assembly on a regular basis.

Departments of the Australian Government[]

- Ministère des finances (Ministry of Finance, responsible for budget and revenue))

- Ministère de l'intérieur (Ministry of the Interior, responsible for law enforcement, civil defence, identity documents and elections administration)

- ministère de la Défense (Ministry of Defence, responsible for the armed forces and partial responsibility for law enforcement (Gendarmerie)

- Ministère des Affaires Étrangères (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, responsible for foreign relations)

- Ministère de justice (administration of courts and prisons)

- Ministère des affaires sociales (Ministry of Social Affairs, responsible for administering welfare)

- Ministère de l'emploi et des relations industrielles (Ministry of Employment and Industrial Relations, responsible for labour market regulation and disputes)

- Ministère de technologie (Ministry of Technology, responsible for promoting Australian technology and administering Australia's nuclear programme)

- Ministère d'instruction publique (Ministry of Public Instruction, responsible for schools and universities)

- Ministère de la protection d'Envrionmental (Ministry of Environmental Protection, responsible for environmental protection)

- Ministère de nourriture, d'agriculture, et de pêche (Ministry of Food, Agriculture & Fisheries, responsible for food safety, agricultural regulation, and fisheries administration)

- Ministère de la Santé (Ministry of Health, responsible for the hospitals and national health insurance)

- Ministère de communication et de culture (Ministry of Communication and Culture, responsible for the arts, promoting and protecting French Australian culture, the ICT industry, and the media)

- Ministère de l'immigration et de la citoyenneté (Ministry of Immigration and Citizenship, responsible for immigration and naturalisation)

- Ministère du développement territorial (Ministry of Territorial Development, responsible for public works, the transport industry, national infrastructure, and housing)

- Ministère des ressources, d'industrie et de tourisme (Ministry of Resources, Industry and Tourism, responsible for promoting and regulating most Australian industries, its minerals sector, and tourism)

Legislative[]

The legislative powers of the Australian government are vested in the Parlement d'Australie (Parliament of Australia) consisting of the Assemblée nationale d'Australie and the Sénat d'Australie. Legislation starts in the National Assembly, and is subject to two readings before it is moved for formal passage. After that, the bill moves to the Senate where it has one reading. If it fails it is passed back to the National Assembly for amendment (unless it is a bill of self-perpetuation to extend the National Assembly beyond its constitutional term, in that event the bill is simply defeated in the Senate). If it passes in the first vote, it goes to the President for signature into law. If it fails at the second vote, the bill goes to a combined sitting of the National Assembly and Senate. If it fails then, the government can either drop the bill or the President can dissolve Parliament and call elections (historically, this has never happened).

Assemblée nationale d'Australie[]

The Assemblée nationale d'Australie (National Assembly of Australia) is the lower house of the Parlement d'Australie. It consists of 150 members known as députés (deputies) elected to serve single-member electorates. The National Assembly has three year terms. Most legislation is initiated in the Assemblée nationale d'Australie by the government party. Only once in Australian history has the party of the President not held a majority in the National Assembly (1975-76)

Sénat d'Australie[]

The Sénat d'Australie (Senate of Australia) is the upper house of the Parlement d'Australie. The Senate has 82 members (10 for each province, 2 for the collectivités d'outre-mer (Overseas Collectivities)). The provincial members are elected by proportional election by all voters in a province. The 2 COM Senators are appointed by the President and cannot vote. The Senate cannot initiate legislation or veto any bill apart from a bill of self-perpetuation. It can impeach the President and has done so once (the 1976 impeachment of Guy Willmot).

Political Parties[]

- Parti libéral-démocrate d'Australie (Liberal Democratic Party of Australia): a liberal party, favouring less government intervention in economics, civil liberties, a strong defence, and strong enforcement of criminal laws. Its philosophy is sometimes called Meignotisme after its founder Robert Meignot. The Liberal Democrats have been the most successful party of the Second Republic. The are usually called "les libéraux".

- Parti national-républicain d'Australie (National Republican Party of Australia): a right-wing party formed by the military officers who deposed the First Republic. It favours dirigisme in economic affairs, social conservatism, and a foreign policy of "grandeur". The are usually called "Gaullists".

- Parti socialiste d'Australie (Socialist Party of Australia): a left-wing party favouring protection of certain groups in the economy, tariffs against imports, and a large welfare state. In foreign policy, they oppose military intervention and favour aid grants. They are usually called "les socialistes". The Socialist Party dates back to the First Republic and is the oldest major party in Australia.

- Partie agricole d'Australie (Agricultural Party of Australia): a populist party that stands for protection of farmers. They favour tariffs, import quotas, and subsidies. Like the Socialists, the Agricultural Party dates back to the First Republic. They are often called l'agrariennes.

Judiciary[]

Administrative Divisions[]

Australia is divided into Provinces, and each Province is divided into Departments. The Departments are divided into Arrondissements, and some of the larger Arrondissements are divided into Cantons.

There are also Overseas Collectivities.

Provinces[]

- Australie-Tropicale (Tropical Australia)

- Côte d'Azur de Sud (Azure Coast of the South)

- Terre d'Bonaparte (Bonaparte Land)

- Nouveau Bretagne (New Brittany)

- Tasmanie (Tasmania)

- Australie-Méridionale (South Australia)

- Australie-Occidentale (Western Australia)

- Australie-Nordique (Northern Australia)

Overseas Collectivities[]

- Île de Noël

- Îles Cocos (Keeling)

- Territoire antarctique australien

- Nouvelle-Calédonie (New Caledonia)

- Territoire des îles Wallis-et-Futuna (Territory of the Wallis and Futuna Islands)